Tobacco products are one of the most heavily marketed consumer products in the U.S. In 2022, the latest year for which information is available, the five largest cigarette manufacturers spent a total of $8.01 billion—or close to $22 million dollars a day—to promote and advertise their products.1 The five largest smokeless tobacco manufacturers spent $572.7 million on advertising and promotion in 2022.1 The 2021 Federal Trade Commission report (FTC) on e-cigarettes and advertising found that $859.4 million was spent on e-cigarette advertising and promotion in 2021 up from $768.8 million in 2020. 2

Only a few states are funding their tobacco control programs at the levels currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), meaning that tobacco company marketing efforts are largely occurring without effective, well-funded state tobacco control programs to respond.

What do the major cigarette companies spend their marketing dollars on?

- The largest single category of marketing and promotional expenditures in 2022 was price discounts paid to cigarette retailers and wholesalers to reduce the cost of cigarettes to the consumer. These categories combined accounted for close to 86% ($6.88 billion) of expenditures.1 The price of cigarettes has a very significant effect on youth smoking. Every 10% increase in the price of cigarettes reduces youth consumption by 7%.3 Price discounts and retail value-added promotions can negate the impact of state tobacco tax increases.

Example of advertising natural products

How have e-cigarettes changed Tobacco Industry Marketing?

- E-cigarettes have seen continued high sales in the past several years. E-cigarette sales increased from $2.394 billion in 2020 to $2.763 in 2021.2 There continues to be significant shifts in the how the e-cigarette industry uses its marketing dollars, particularly when it comes to price discounting.2

- Following the extension of FDA’s prohibition on tobacco sampling to include e-cigarettes in 2016, companies began offering discounted e- cigarettes for as low as $1 to avoid the law.4 The FTC found that price discounting for e-cigarettes reached a record high in 2021 of $261.6 million.2 This was during the same period when FDA released an enforcement policy guidance, prioritizing enforcement against certain types of flavored e-cigarettes, except menthol products. 4

- Studies indicate consumers' response to price changes for tobacco products have a stronger response from youth than adults.4 This increases the risk of e-cigarettes for youth and the risk of addiction.

- The sale of Menthol cartridges increased accounting for 16.7% in 2019, 63.5% in 2020, and 69.2% in 2021. 2 Mint or menthol disposable devices represented 49.8% of all disposable devices sold in 2021.2

How does tobacco product advertising affect youth smoking?

- Tobacco companies have targeted kids and teens for decades spending millions of dollars in marketing techniques.5 Schemes such as marketing candy, celebrity endorsement and misleading health claims have contributed to tobacco youth addiction.

- A 2018 study found that the top three preferred tobacco brands among 72.1% of current middle and high school student smokers were also the top three most advertised brands.6

- The 2012 Surgeon General's report on preventing tobacco use among youth concluded that there is a causal relationship between tobacco industry advertising and promotional efforts, and the initiation and progression of tobacco use among young people. 7

- A 2010 study found that youth who reported having a favorite tobacco ad at the start of the study in 2003 were 50% more likely to have smoked five years later in 2008. After the start of the R.J. Reynolds “Camel No. 9” advertising campaign in 2007, the proportion of girls with a favorite ad increased by 10 percentage points. 8

- A 2007 study found that retail cigarette marketing increased the likelihood that youth would start smoking; cigarette pricing strategies contributed to increases all along the smoking continuum, from initiation and experimentation to regular smoking; and cigarette promotions increased the likelihood that youth would move from experimentation to regular daily smoking. 9

- A 2014 study found that 41% of 12- to 13-year-olds were receptive to at least one tobacco advertisement, with half of older adolescents receptive to at least one tobacco advertisement. Highest receptivity was for e-cigarettes followed by cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and cigars. 10

Example of advertising candy flavors.

How do tobacco companies target priority and vulnerable populations?

- Certain tobacco products are advertised and promoted disproportionately to specific racial or ethnic groups. A 2019 study found that Non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaska Natives had a higher prevalence of exposure to retail tobacco ads, mail, and email marketing compared to non-Hispanic whites. 11 Advertising and promotion of cigarette brands with names such as Rio, Dorado and American Spirit have been marketed toward Hispanics, American Indians and Alaska Natives.12

Advertising for tobacco products historically has been more prevalent in African American communities. An analysis of available studies to date in 2007, found that the odds that any given billboard/outdoor signage advertisement was smoking-related were 70% higher in predominantly African American neighborhoods than in predominantly white neighborhoods, and there were 2.6 times as many tobacco advertisements per person in African-American areas.13

Tobacco companies have aggressively marketed menthol cigarettes to African American communities since the 1950s. Advertising of menthol cigarettes and flavored little cigars and cigarillos is more prominent in neighborhoods with a larger African American demographic and lower incomes.14 The efforts of Big Tobacco to market and sell menthol cigarettes to Black individuals have contributed to significant health disparities: over 80% of Black individuals who smoke use menthol cigarettes. Tobacco use is the number one cause of preventable death among Black individuals, claiming 45,000 Black lives every year. 15

The tobacco industry was one of the first to develop marketing materials specifically targeting the LGBT community. The most infamous example of this was so-called Project SCUM (for "Subculture Urban Marketing"), a plan by RJ Reynolds in the mid-1990s to market their Red Kamel brand to gay men in San Francisco's Castro District and homeless people in the city's Tenderloin neighborhood.16

Ads for smokeless tobacco frequently depict rugged "manly" images of cowboys, hunters and race car drivers that are carefully placed in the media and retail outlets most likely to reach rural audiences. It seems to work well; a 2012 study of boys and men in Appalachian Ohio found that the participants viewed smokeless tobacco use as a rite of passage in the development of their masculine identity, and a key to acceptance into male social networks.17

A study found that tobacco products are sold at lower prices in areas with lower social economic status (SES)18 and to children, increasing health disparities and tobacco use in these populations19. The tobacco industry strategically prices their products to these communities, including price discounting using couponing and lower prices for those with low education.20

How do tobacco companies market their products to women?

- Women also have been extensively targeted by tobacco marketing. Such marketing is dominated by themes of an association between social desirability, independence, weight control and smoking messages conveyed through advertisements featuring slim, attractive and athletic models.21 As a result of this successful targeting, disease risks from smoking have risen dramatically for women over the past 50 years and are now equal to those for men for lung cancer.22

- As early as the 1920s, tobacco advertising began incorporating slogans like “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” and “To read the advertisements these days, a fellow’d think the pretty girls do all the smoking” in an effort to associate smoking with a slender physique. During this same time the number of women smoking increased significantly among those 18 through 25 years old. 21

- An analysis of previously confidential tobacco industry documents found that tobacco companies have been targeting specific sub-groups of women since at least the 1970s, including military wives, inner-city minority women, and older discount-sensitive women. Tactics included offering discounts by mail and at the point of sale, and using more direct, literal language in advertising and marketing materials. These tactics are or could be still in use today.23

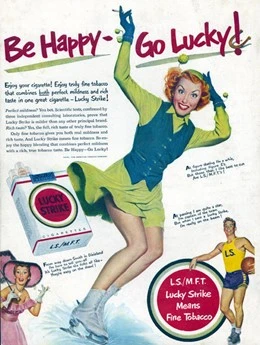

Example of marketing to women.

What federal laws govern tobacco product advertising and promotion?

- In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued its final “deeming” rule, which brought all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, cigars and other products under FDA regulation of tobacco products. This included some advertising and promotional restrictions, including the prohibition on free samples of tobacco products.24

- In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a final rule that placed several restrictions on marketing and promotion of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, including prohibiting brand name sponsorship of athletic, musical, or other social or cultural events, prohibiting the sale or distribution of certain items with cigarette and smokeless tobacco brands or logos and prohibiting free samples of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco except in “a qualified adult-only facility” for smokeless tobacco.25

- The 2009 legislation giving the FDA the authority to regulate tobacco products, known as the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, also removed part of the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act (FCLAA) that had preempted states and local governments from restricting the time, place and manner of cigarette advertising and promotion.26

- The FCLAA also prohibits certain means of advertising concerning cigarettes, such as advertising on radio and television.26

Images courtesy of TrinketsAndTrash.org

-

Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette Report for 2022. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; 2022.

-

Federal Trade Commission. E-Cigarette Report for 2021. Issued 2024.

-

Tauras JA, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Effects of Price and Access Laws on Teenage Smoking Initiation: A National Longitudinal Analysis. ImpacTeen - YES! Research Papers. April 2001.

-

Federal Trade Commission E-Cigarette Report for 2019-2020. Issued 2022.

-

National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco control monograph no. 19. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Cancer Institute; 2008. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf

-

Perks SN, Armour B, Agaku IT. Cigarette Brand Preference and Pro-Tobacco Advertising Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67:119–124. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6704a3

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2012.

-

Pierce JP, Messer K, James LE, White MM, Kealey S, Vallone DM, Healton CG. Camel No. 9 Cigarette Marketing Campaign Targeted Young Teenage Girls. Pediatrics 2010; 125(4):619-26.

-

Slater, SJ, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM. The Impact of Retail Cigarette Marketing Practices on Youth Smoking Uptake. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine May 2007; 161(5):440-45.

-

Pierce JP, Sargent JD, White MM, et al. Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising and Susceptibility to Tobacco Products Among Youths. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6)

-

Cranford JA, Eisenberg D, Sarafin RE, Zucker RA. Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences among students with a disability: Findings from a national study. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(14):2316-2328. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1664589.

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. 1998.

-

Primack BA, Bost JE, Land SR, Fine MJ. Volume of Tobacco Advertising in African American Markets: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health Rep. Sep-Oct 2007; 122(5):607-615.

-

Unfair and Unjust Practices and Conditions Harm African American People and Drive Health Disparities | Smoking and Tobacco | CDC

-

American Lung Association. What’s Happening with Menthol Cigarettes? American Lung Association Blog. Published April 29, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.lung.org/blog/whats-happening-with-menthol-cigarettes

-

Stevens P, et al. An Analysis of Tobacco Industry Marketing to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Populations: Strategies for Mainstream Tobacco Control and Prevention. Health Promotion Practice. 2004; Supplement to Vol. 5(3).

-

Nemeth JM, Liu ST, Ferketich AK, Kwan MP, Wewers ME. Factors Influencing Smokeless Tobacco Use in Rural Ohio Appalachia. Journal of Community Health. Dec 2012; 37(6):1208-17.

-

Guindon GE, Fatima T, Abbat B, et al. Area-level differences in the prices of tobacco and electronic nicotine delivery systems - A systematic review. Health Place 2020; 65:102395.

-

Varian HR. Chapter 10 Price discrimination. In: Handbook of industrial organization, 1198: 597–654.

-

Levy DT, Liber AC, Cadham C, et al. Tob Control Epub ahead of print: [please include Day Month Year]. doi:10.1136/ tobaccocontrol-2021-056971

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2001.

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014.

-

Brown-Johnson CB, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the USA. Tob Control 2014;23: e139-e146

-

Products, C. for T. (2020, January 30). Advertising and Promotion. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-guidance-regulations/advertising-and-promotion

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco to Protect Children and Adolescents. June 22, 2010.

-

Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act. 15 U.S. Code §§ 1331 to 1341.

Page last updated: September 10, 2024